Born into slavery, Doshia Green lived at 822 E. South Street in 1912.

By Tana Mosier Porter from the Summer 2010 edition of Reflections From Central Florida

Formerly enslaved people founded Orlando’s first African American community about 1880, when Sam Jones and his wife, Penny, settled along the banks of Fern Creek, about a mile east of Orlando’s downtown. Orlando’s promise of growth and prosperity attracted other African Americans hoping to find new lives in Florida.

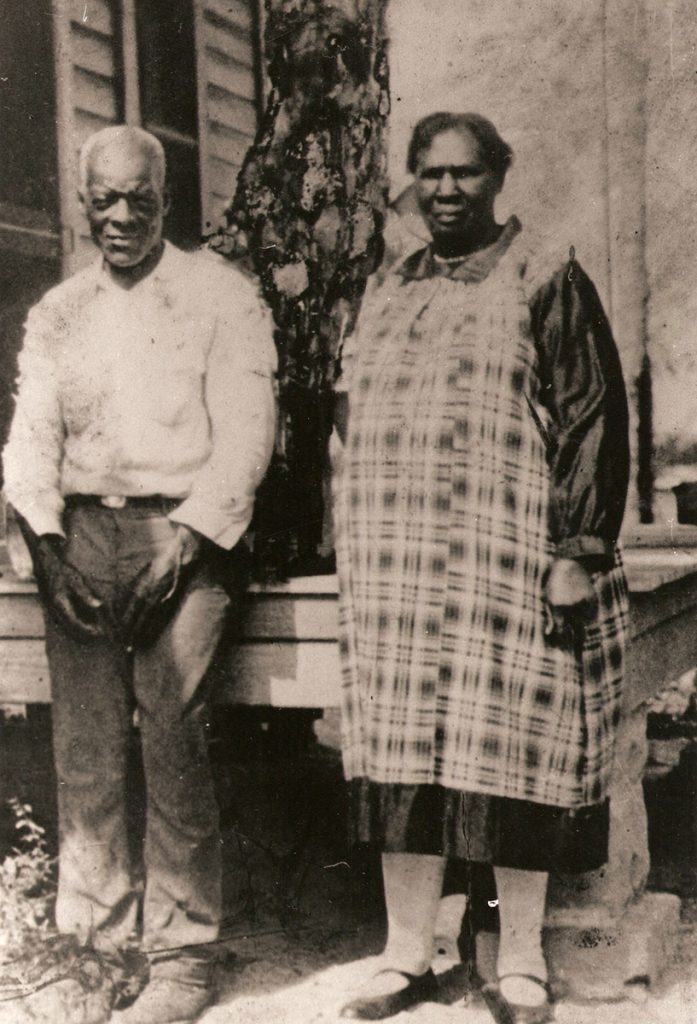

Some worked on building the South Florida Railroad, while others served in the homes and business establishments of the white residents. Milo Cooper, one-time body servant for Jefferson Davis, lived in the settlement and operated a barbershop on East Pine Street in 1884. Mose Paine lived there with his wife, Ellen, a cook at the Duke Hall rooming house. Residents established Mount Olive CME Church on East South Street in 1886.

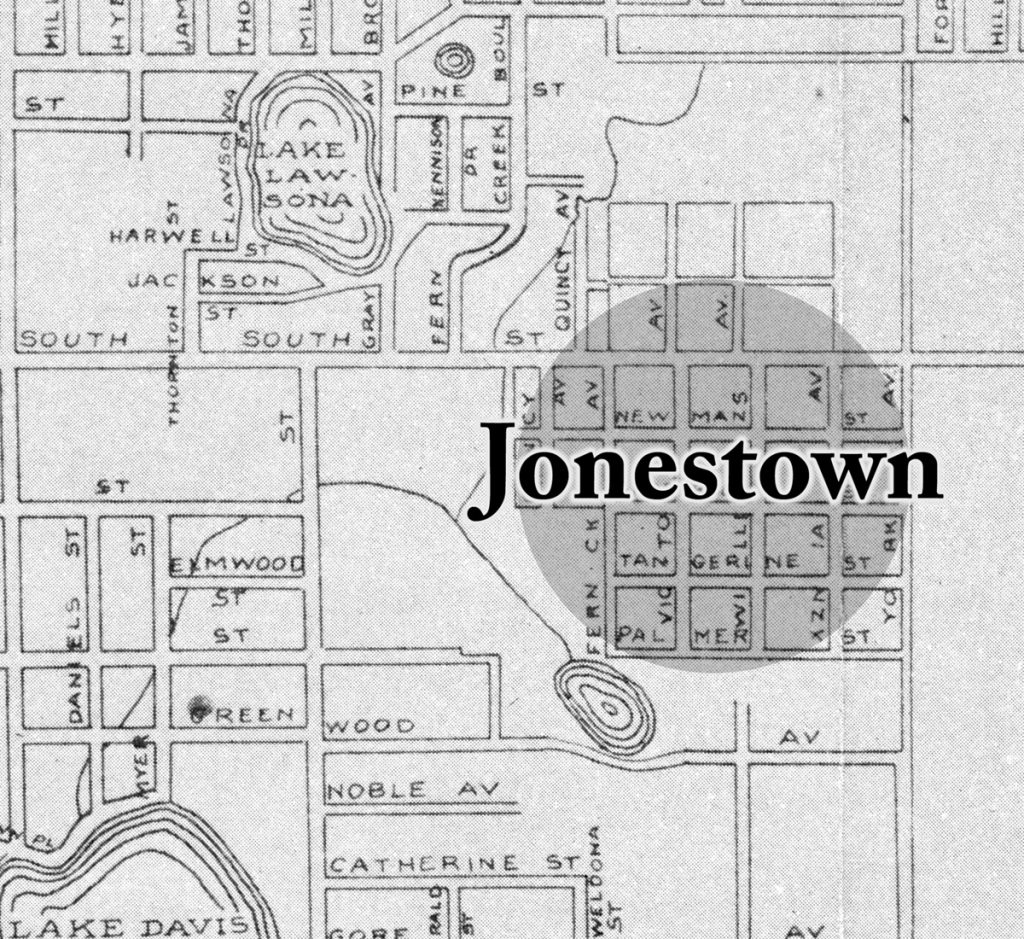

Records suggest the settlement was originally called Burnett Town, but James Magruder, a white businessman, changed the name to Jonestown in 1890, when he developed a subdivision on South Street. Twenty-one families lived in Jonestown in 1891. M. Duncan and E.F. Wooden ran grocery stores. Isaac Cleveland was a carpenter, and Alex Varner a wagoner. Fifteen others, including Sam Jones, are listed as “laborers” in Orlando’s 1891 city directory.

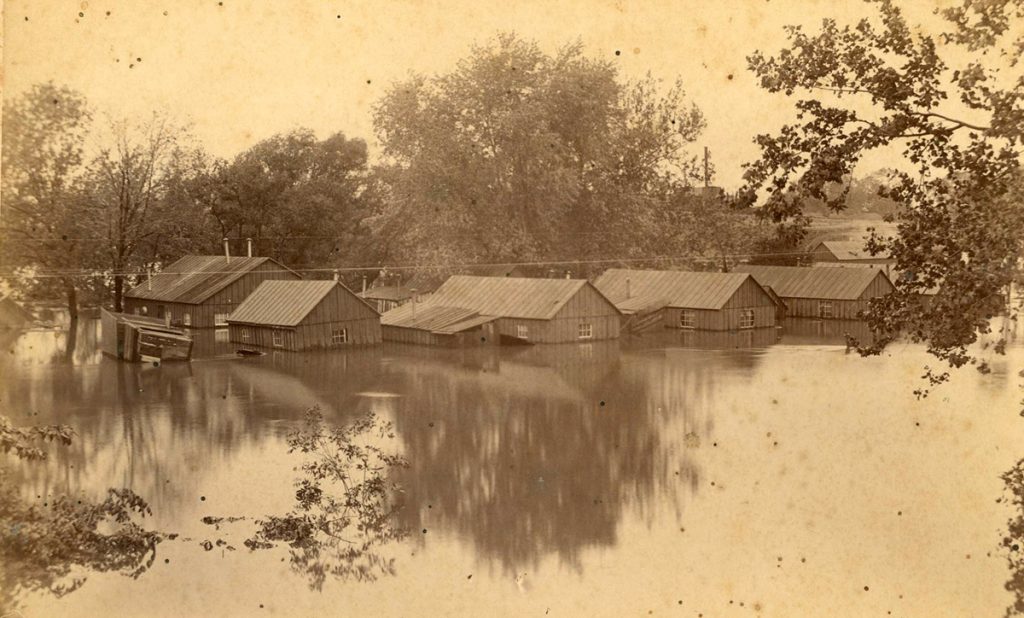

Jonestown flooded in 1904 and whenever the sinkhole near Greenwood Cemetery overflowed.

Flood and re-emergence

In those days, African Americans typically lived in on the outskirts of cities, separated from whites but close enough to do their work. Jonestown occupied a low area near Greenwood Cemetery. During the rainy season of 1904, the sinkhole at the cemetery overflowed and, with nearby lakes Davis, Lancaster, Cherokee, and Lucerne, flooded Jonestown to the rafters of the one-story houses

Local historian William R. O’Neal wrote years later in his Memoirs that the owners had to evacuate their “prosperous, law-abiding community with its church and store.” Drainage wells eventually solved the flooding problem, but, according to O’Neal, Jonestown residents who had escaped the flooding had by then found other dwellings and did not return. The 1907 Orlando city directory makes no mention of Jonestown.

By 1916, the community had reappeared. Fewer residents owned their homes by 1916, when African Americans inhabited 37 houses on South Street alone, 21 of them identified in an insurance rate book as “Colored Tenant Dwelling.” L. Burnette owned at least five, and Magruder twelve. Two stores operated by African Americans and the Mount Olive CME Church occupied buildings on East South Street.

Jonestown, the only developed area east of Mills Avenue in 1925, boasted more than 70 houses from the east bank of Fern Creek to Williams Avenue, north to Jackson Street and south to Anderson Street. One school, two churches, and six commercial establishments served the residents of the community. The buildings, all of them frame, tended to be very small. The Mount Olive CME Church occupied a frame building, with a heating stove and oil lamps. The “Colored School” on Newman Avenue had an oil stove for heat, but no lights. The Bethlehem Baptist Church on Quincy Avenue had neither heat nor lights.

“Aunt Ellen” Paine cooked for many years at Duke Hall rooming house in Orlando.

“Complete removal”

When a house on South Street occupied by an African American family burned early in 1939, work began on rebuilding it. But a delegation of white residents protested to city officials, citing the poor condition of neighboring structures. The city withdrew the building permit.

Two weeks later, in February, the Orlando Morning Sentinel reported that Orlando had a plan for the “complete removal” of Jonestown. A low-cost housing project for whites would replace the “existing Negro dwellings,” thus eliminating what the writer called “a cancer which has long gnawed at the vitals of various city administrations.”

The Morning Sentinel endorsed the plan in an editorial the next day: “For long, Jonestown has been a subject of much concern to the white population which encircles it,” the paper stated. The African Americans themselves would be happier in southwest Orlando with “others of their race.” Residents of the white subdivisions that surrounded Jonestown by 1939 no longer accepted African Americans in that location, and the Jonestown real estate, originally remote and undesirable, now stood in the way of city expansion.

At the time, Jonestown comprised 76 residences, the Mount Olive CME and Bethlehem Missionary Baptist churches, the East Orlando School, and a grocery store. At least 19 residents owned their homes. Reluctant to leave behind a half-century of tradition and community on the east side of Fern Creek, and probably in doubt about where they could afford to go, some residents stayed in their homes. When another sinkhole opened in October 1939 on Quincy Street, the city council discussed ways of forcing Black residents to move out of the area, suggesting that the streets be abandoned or that the city buy more land in the area. One commissioner suggested “punching” another sinkhole, the Morning Sentinel reported, “and maybe they’ll all move out.”

Newspaper reports seemed to hold out the promise that African American population would all move into the Griffin Park public housing project, dedicated on the west side of Orlando on September 8, 1940, but records show that no one who lived in Jonestown in 1939 or 1940 lived in Griffin Park in 1941.

In fact, despite demands that the remainder of Jonestown residents leave and move to the African American district in southwest Orlando, and despite construction of Reeves Terrace public-housing project for whites in the north section of Jonestown, people stayed in their homes. A number of African American families appear to have moved from the site of Reeves Terrace to other parts of Jonestown. By 1943, though, several residents of Moore’s Court, which had been vacated to build Reeves Terrace, had moved to Griffin Park.

African Americans gradually gave up Jonestown, leaving just 11 families, all in the southern part of the community in 1951, the last year the city directory indicated the race of residents. In 1955, only the Mount Olive CME Church and about a half-dozen houses remained on South Street, and by the 1962 death of Jonestown’s last resident, Mrs. Virginia Spellman, who had lived for more than 30 years in a house she owned on East South Street, the historic community had long ago ceased to exist.

Jonestown’s first residents, Sam Jones and his wife, Penny.

A 1924 map shows the location of Jonestown.

Sources: In addition to newspapers, city directories, and insurance maps, sources include publications of the Central Florida Society of Afro American Heritage; LeRoy Argrett, Jr., A History of the Black Community of Orlando, Florida (1991); Eve Bacon, Orlando: A Centennial History (1976); and W.R. O’Neal’s “Memoirs of a Pioneer,” available in the Joseph L. Brechner Research Center of the Orange County Regional History Center. Researchers can also find a type-script of this article, with full citations and footnotes, in the research library.